‘The Black Dog’ is a famous phrase or analogy for depression. Its fame stems from its usage by Winston Churchill as publicised by his doctor, Charles Wilson the 1st Baron Moran. Moran published Winston Churchill: The struggle for survival, 1940-1965 in 1966 to much controversy about his apparent breach of doctor-patient confidentiality. Within the 900-page volume he spoke candidly about Churchill’s struggles with depression, something he referred to as Churchill’s ‘black moods’ or the ‘Churchill meloncholia’. He gathered from Churchill’s friends that there was a belief that this depressive strain was hereditary, passed down through the Dukes of Marlborough, but happily for Winston tempered by the ‘bright, red American blood’ from his mother which ‘cast out the Churchill melancholy’.1 Churchill’s friend Brendan Bracken (who purposefully fostered rumours that he was Winston’s illegitimate son) traced this depressive strain to Churchill’s childhood, when he ‘deliberately set about to change his nature, to be tough and full of rude spirits’. ‘You see’, he continued, ‘Winston has always been a “despairer”… Winston has always been moody; he used to call his fits of depression the “Black Dog”.’2

‘The Black Dog’ is a famous phrase or analogy for depression. Its fame stems from its usage by Winston Churchill as publicised by his doctor, Charles Wilson the 1st Baron Moran. Moran published Winston Churchill: The struggle for survival, 1940-1965 in 1966 to much controversy about his apparent breach of doctor-patient confidentiality. Within the 900-page volume he spoke candidly about Churchill’s struggles with depression, something he referred to as Churchill’s ‘black moods’ or the ‘Churchill meloncholia’. He gathered from Churchill’s friends that there was a belief that this depressive strain was hereditary, passed down through the Dukes of Marlborough, but happily for Winston tempered by the ‘bright, red American blood’ from his mother which ‘cast out the Churchill melancholy’.1 Churchill’s friend Brendan Bracken (who purposefully fostered rumours that he was Winston’s illegitimate son) traced this depressive strain to Churchill’s childhood, when he ‘deliberately set about to change his nature, to be tough and full of rude spirits’. ‘You see’, he continued, ‘Winston has always been a “despairer”… Winston has always been moody; he used to call his fits of depression the “Black Dog”.’2

It seems likely that Churchill’s use of the phrase has a deeper antecedent. Churchill’s private secretary John Colville believed that he had learned the phrase from a childhood nurse:

Of course we all have moments of depression, especially after breakfast. It was then that [Lord] Moran [Churchill’s doctor] would sometimes call to take his patient’s pulse and hope to make a note of what was happening in the wide world. Churchill, not especially pleased to see any visitor at such an hour, might excuse a certain early-morning surliness by saying, “I have got a black dog on my back today”. That was an expression much used by old-fashioned English nannies. Mine used to say to me if I was grumpy, “You have got out of bed the wrong side” or else “You have got a black dog on your back”. Doubtless, Nanny Everest was accsutomed to say the same to young Winston Churchill. But, I don’t think Lord Moran ever had a nanny and he wrote pages to explain that Churchill suffered from periodic bouts of acute depression which, with the Churchillian gift for apt expression, he called “black dog”. Lady Churchill told me she thought the doctor’s theory total rubbish…3

Indeed, the phrase ‘the black dog has walked all over him’ or ‘he has the black dog on his back’ is an old one, referring to someone experiencing a melancholic or sullen mood (OED). The idea of the black dog as an ill omen or bad luck has very long roots. Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable notes that Horace called the sight of a black dog with its pups an ‘unlucky omen’. A marvellous article by Paul Foley which delves deep into the etymology of the ‘black dog’ phrase notes that this was likely based on a mistranslation, but nonetheless Horace’s evocation of the black dog as a dark companion who broods and follows is a poignant one:

No company’s more hateful than your own

You dodge and give yourself the slip; you seek

In bed or in your cups from care to sneak

In vain: the black dog follows you and hangs

Close on your flying skirts with hungry fangs.4

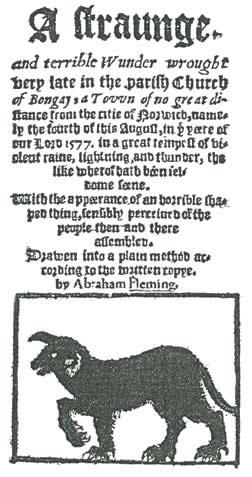

In a broadly Christian context, meanwhile, the Black Dog has long been associated with the devil, and folklore in England and Ireland is known to refer to terrifying, large black dogs with red eyes that stalk unaccompanied travellers at night. This was of course the roots of Conan Doyle’s Hound of the Baskervilles in which Sherlock Holmes’s stubborn rationalism wins out over the dark superstititions of the Devonshire moors. Black dogs have long been considered gaurdians of the underworld – from the most famous Cerberus, to more local variants such as the Welsh Cŵn Annwn, the Manx Moddey Dhoo (also known as Mauthe Doog) or the Barghest of north-east England. Interetingly, Shuck, the ghostly dog who is said to haunt the East Anglian coastline, seems to derive its name from scucca, meaning devil, and/or skuh, meaning to terrify (OED). A Dictionary of English Folklore suggests that ‘The many phantom dogs of local legend are almost invariably large black shaggy ones with glowing eyes; those which appear only in this form are simply called “the Black Dog”, whereas those that change shape often have some regional name such as bargest, padfoot, or Shuck.’ The changing shape of such local variants brings the legends back to a devilish connection, the devil being commonly thought able to change his form. In the famous words of Shakespeare, ‘The devil hath power / To assume a pleasing shape’ (Hamlet, Act 2 scene 2).

For most, though, the particular association between the Black Dog and the idea of depression and melancholy comes from Samuel Johnson and his correspondence with a friend, Mrs Thrale. Johnson has imprinted his version of the Black Dog onto the historical record because of his fame, eloquence and inveterate letter-writing. Given his love of language (as the compiler of the first Dictionary of the English Language) it is perhaps fitting that his use of the term seems to have amalgamated these many forms, from the suggested ill-omens of Horace, to the devilish connotations of local folklore. ‘The black dog I hope always to resist, and in time to drive, though I am deprived of almost all those that used to help me’, wrote Johnson to Mrs Thrale on 28th June 1783.

When I rise my breakfast is solitary, the black dog waits to share it, from breakfast to dinner he continues barking, except that Dr Brocklesby for a little keeps him at a distance… Night comes at last, and some hours of restlessness and confusion bring me again to a day of solitude. What shall exclude the black dog from a habitation like this?

Loneliness, fear and confusion jump off the page from this passage across the intervening centuries. The Black Dog lurks and lumbers, begs and worries (in the sense of a dog worrying sheep I suppose). It haunts and glares and follows and disturbs. It is the phantom dog of folklore lurking in the shadows, the ill-omened dog of Horace flying at your skirts, and the heavy dog of meloncholy weighing down your back. Johnson’s solitary musings are a painful reminder that the black dog thrives in isolation, but also enforces its existence, making social intercourse difficult, and asking for help nigh-on impossible. Luckily the White Dog doesn’t need to be asked.

1 Lord Moran, Winston Churchill: The struggle for survival, 1940-1965 (London: Constable, 1966), p. 745.

2 Lord Moran, Winston Churchill: The struggle for survival, 1940-1965 (London: Constable, 1966), p. 745.

3 Colville J (1995) The personality of Sir Winston Churchill ( = Crosby Kemper Lecture, 24 March 1985). In: Kemper RC (ed), Winston Churchill: Resolution, defiance, magnaminity, good will (Columbia: University of Missouri), pp. 108-125. See also Gilbert M (1994) In search of Churchill. A historian’s journey (London: Harper Collins), pp. 209f.

4 J. Conington, The satires, epistles, and Art of Poetry of Horace (London: George Bell & Sons, 1863), p. 90. [Cited in Paul Foley, ‘“Black dog” as a metaphor for depression: a brief history’, p. 3.